Cloud Snooper Attack - Hiding Malicious Commands in Web Traffic to AWS Servers

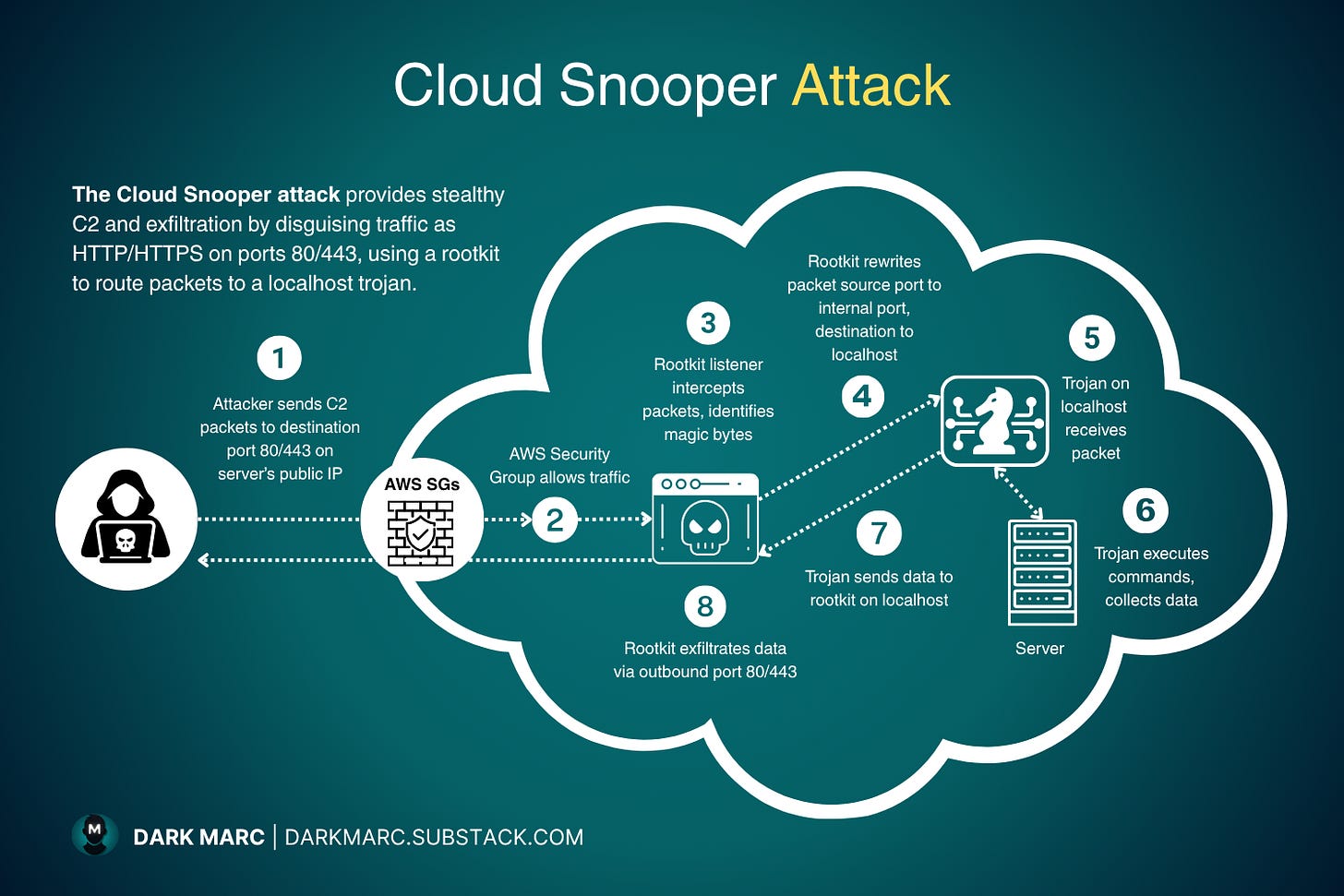

The Cloud Snooper attack is a method for attackers to maintain hidden command-and-control (C2) access to compromised cloud servers, targeting AWS EC2 instances.

The attack exploits how cloud firewalls (AWS Security Groups) are configured and uses malware installed on the target server to secretly communicate with attackers while blending into normal web traffic.

The Core Problem This Attack Exploits

Most web servers on AWS are configured to allow only two types of incoming traffic:

Port 80: HTTP (regular web traffic)

Port 443: HTTPS (encrypted web traffic)

This configuration is enforced by AWS Security Groups (SGs), which act as virtual firewalls controlling what traffic can reach your cloud instances. The Security Group checks every incoming packet and asks: “Is this going to port 80 or 443?” If yes, it allows it through. If no, it blocks it.

This seems secure, only web traffic gets in. But the Cloud Snooper attack turns this security measure into an opportunity.

The Initial Compromise

The Cloud Snooper attack cannot happen without the attacker first compromising the target server and installing malware.

Before any C2 communication begins, attackers must gain access through traditional methods:

SSH brute-forcing: Guessing weak passwords on SSH (remote login) services

Supply chain attacks: Compromising software updates or dependencies

Exploiting vulnerabilities: Using security flaws in applications or traffic filters

Phishing or credential theft: Tricking administrators into revealing access

Once inside, the attacker installs two pieces of malware:

A rootkit: Stealth software that hides the attacker’s presence

A backdoor/trojan: Software that executes the attacker’s commands

Only after this installation is complete can the Cloud Snooper technique work.

Key Malware Components

The Rootkit: The Stealth Engine

A rootkit is malware designed to remain hidden while providing privileged access. Think of it as an invisibility cloak for malicious software.

What it does:

Hides processes: Makes malicious programs invisible to system monitoring tools (you can’t see them in task manager equivalents)

Hides network activity: Conceals suspicious network connections from detection tools

Intercepts system calls: Modifies how the operating system reports information, essentially making it “lie” about what’s running

Maintains persistence: Ensures the attacker’s access survives reboots and security scans

Routes traffic internally: Acts as a traffic director, intercepting and redirecting network packets

In Cloud Snooper, the rootkit has two components:

Listener: Monitors all incoming network traffic, watching for attacker communications

Packet rewriter: Modifies network packets to route them to the right destination

The Backdoor Trojan

The backdoor trojan is a separate program that actually performs the attacker’s instructions. It’s called a “trojan” because it masquerades as legitimate software while harboring malicious functionality.

What it does:

Executes shell commands (like a remote terminal)

Steals credentials and access keys

Exfiltrates sensitive files and data

Conducts reconnaissance of the system

Facilitates lateral movement to other systems

Why separate from the rootkit?

Modularity: The rootkit provides infrastructure (hiding, routing) while the trojan provides functionality (execution)

Stability: Kernel-level rootkit code is complex; keeping command execution separate reduces crashes

Flexibility: Attackers can update the trojan without touching the more dangerous rootkit installation

How the Attack Works

Step 1: Attacker Sends Disguised Commands

The attacker sends malicious command-and-control packets from their remote location to the compromised server. These packets are crafted to look exactly like normal web traffic:

Destination port: 80 or 443 (appearing as legitimate HTTP/HTTPS)

Hidden commands: Embedded within what looks like normal web requests

Magic bytes: Secret markers hidden in HTTP headers or payloads that identify this as attacker traffic (like a secret handshake)

Example of what this might look like:

Normal web request:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

Host: example .com

Attacker’s C2 packet (looks similar):

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

Host: example .com

X-Session-ID: 41424344 ← Magic bytes signaling “this is C2”

[Hidden command data in body]Step 2: AWS Security Group Allows Traffic Through

The AWS Security Group examines the incoming packet:

Checks destination port, sees port 80 or 443

Compares against rules, web traffic is allowed

Allows packet through, it looks completely legitimate

The Security Group isn’t compromised or broken, it’s simply doing its job. The attacker is exploiting the fact that the SG can only see basic packet information (ports, IPs) but cannot inspect the packet’s actual content to determine if it’s malicious.

Step 3: Rootkit Intercepts and Identifies the Packet

Here’s where the critical mechanism operates. The packet arrives at port 80 or 443 where the legitimate web server (like nginx or Apache) is listening. But before the web server can receive it, the rootkit intercepts it.

How interception works: The rootkit is able to see traffic before applications receive it:

Kernel-level hooks: Code running in the operating system’s kernel that can intercept network packets

Raw socket sniffing: Low-level network access that captures all packets, regardless of their destination

Packet filtering libraries (like libpcap): Tools designed for network analysis that can capture traffic

The rootkit examines every incoming packet looking for the magic bytes, the secret marker that identifies attacker C2 traffic. When it finds a match:

Regular traffic: Ignored, passed through to nginx normally

C2 traffic with magic bytes: Intercepted and processed

Step 4: The Demultiplexing Problem

Now the rootkit faces a challenge. It has identified an attacker’s command packet, but it can’t simply pass it to the backdoor trojan. Here’s why:

The port conflict problem:

Port 80 is already bound by nginx (the legitimate web server)

“Binding” means nginx has told the operating system “I own port 80, send all port 80 traffic to me”

Only ONE program can bind to a port at a time

The backdoor trojan cannot also listen on port 80, it would create a conflict and fail

Why the trojan can’t just listen on port 80: If the trojan tried to bind to port 80:

Operating system: “Error: Port 80 already in use by nginx”

Trojan fails to start

Attack doesn’t work

The solution: Demultiplexing

Demultiplexing means taking a single input stream and routing it to multiple different destinations based on content.

The rootkit performs demultiplexing:

All traffic arrives at port 80 (single entry point)

Rootkit identifies which traffic is for nginx vs. the trojan

Routes each packet to the appropriate destination

Step 5: Rootkit Rewrites the Packet

To route the C2 packet to the trojan, the rootkit performs packet rewriting:

Original packet:

Source port: [attacker’s random port]

Destination: [Server IP]:80

Rewritten packet:

Source port: 1010 (or 2020, 6060, 7070, 8080, 9999)

Destination: 127.0.0.1:1010

Why these changes?

Why change source port to 1010, 2020, etc.? These ports serve as internal routing codes:

Different ports can signal different command types (multiplexing channels)

Port 1010 might mean “shell commands”

Port 2020 might mean “file exfiltration”

Port 8080 might mean “credential harvesting”

Why change destination to 127.0.0.1?

127.0.0.1 is the “local host” or “loopback” address, it means “this computer”

Traffic sent to 127.0.0.1 never leaves the machine

It’s for internal communication only

Why local host matters for stealth: The legitimate web server (nginx) binds to 0.0.0.0:80, meaning it listens on all network interfaces and is accessible from external networks. In contrast, the backdoor trojan binds to 127.0.0.1:1010, not 0.0.0.0:1010:

127.0.0.1:1010 = only accessible from within the same machine

0.0.0.0:1010 = accessible from any network interface (internal or external)

If the trojan used 0.0.0.0:1010:

AWS Security Group would need a rule allowing port 1010 (suspicious)

Network monitoring would see an unusual listening port

Security scanners would detect it

External attackers could potentially access it directly

By using 127.0.0.1:1010:

Completely invisible to AWS Security Groups (internal traffic only)

No unusual external-facing ports

Only the rootkit can reach it

Maximum stealth

Step 6: Trojan Receives and Executes Commands

The rewritten packet is re-injected into the network stack as if it were a new, local connection. The operating system sees:

Packet to 127.0.0.1:1010

Checks: “Who’s listening on port 1010?”

Finds: Backdoor trojan

Delivers packet to trojan

The trojan receives the command and executes it:

Run system commands

Access files and databases

Steal credentials (SSH keys, AWS tokens)

Extract configuration files

Perform reconnaissance

Set up persistence mechanisms

Enable lateral movement to other systems

Step 7: Trojan Sends Data to Rootkit

After collecting sensitive data, the trojan sends it back to the rootkit via local host connection. This internal transfer prepares the data for external exfiltration.

Step 8: Rootkit Exfiltrates Data

The rootkit receives data from the trojan and handles external transmission:

Rootkit packages data: Embeds it in legitimate-looking HTTP/HTTPS responses

Blends with normal traffic: Exfiltrated data looks like regular web server responses

Passes through Security Group: Outbound traffic on ports 80/443 is typically allowed

Reaches attacker: Data extracted successfully without triggering alerts

The entire exfiltration looks like normal web traffic, perhaps a large file download or API response.

Why This Attack is Effective

Bypasses Multiple Security Layers

Cloud firewall (Security Group): Traffic uses allowed ports (80/443)

Network monitoring: Appears as legitimate HTTP/HTTPS traffic

Process monitoring: Rootkit hides malicious processes

Connection tracking: Uses local host connections (invisible externally)

Port scanning: No suspicious external-facing ports

Maintains Persistent Access

Rootkit ensures survival across reboots

Communication can happen anytime attacker wants

Multiple command channels via different ports

Difficult to detect even with security tools

Blends with Normal Operations

Web servers naturally have high traffic on ports 80/443

Malicious packets hidden among thousands of legitimate requests

No unusual ports or protocols to alert defenders

Timing can match normal traffic patterns

Detection and Prevention

Key defensive measures include:

Monitor for rootkit indicators (hidden processes, kernel modifications)

Inspect local host traffic (uncommon high ports like 1010, 2020)

Use endpoint detection tools that can detect kernel-level hooks

Implement application whitelisting

Monitor for unusual outbound data transfers

Regular security audits and vulnerability patching

Strong SSH security (no password auth, key-based only)

Supply chain security verification

Cloud Snooper is an attack that exploits the gap between network-level security (Security Groups allowing ports 80/443) and host-level compromise (malware already installed).

It demonstrates that perimeter security alone is insufficient. Attackers who gain initial access can abuse legitimate traffic channels to maintain hidden, persistent control while evading detection.

The attack’s effectiveness lies in its simplicity: hide in plain sight by using the very ports that must remain open for legitimate business operations.